Making Waves

Photograph by Hermeet Gill

Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937) had a simple vision — to connect the world through wireless technology

Much of the technology we use today — mobile phones, wifi, GPS, and Bluetooth — can trace its origins back to Marconi’s ideas and devices.

Marconi’s hands-on science experiments explored the unseen world of radio waves.

And in the process, he revolutionised the way the whole world stays connected.

Book a free Museum ticket

Radio Waves

Right now, there are invisible waves of electro-magnetic energy moving all around you

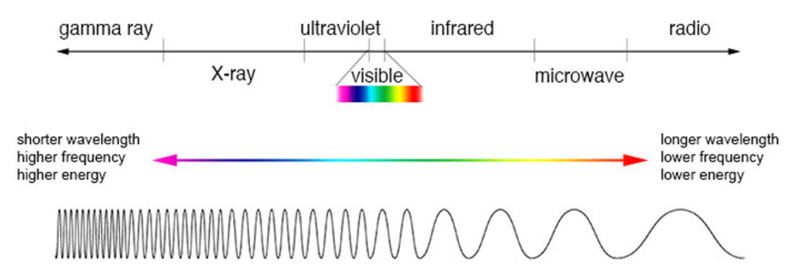

Diagram of electromagnetic spectrum

In the middle of the diagram is visible light, with wavelengths from violet (short) to red (long).

The electromagnetic waves with the smallest wavelengths form x-rays and gamma rays — the longest are microwaves and radio waves.

As wavelength increases, frequency (or the number of waves in a range) goes down.

More Marconi stories

Book a free Museum ticket

The Titanic set sail from Southampton on 10 April 1912, equipped with the best radio technology money could buy

The two wireless operators — Jack Phillips and Harold Bride — worked for the Marconi Company, and used instruments like these.

Alec Bagot, Wireless operator on the RMS Olympic c. 1912

In the critical hours after the Titanic hit the iceberg, their messages — received by 12 ships within range — saved the lives of 705 passengers and crew.

Wireless telegraphy sent messages through the air instead of along wires. That meant, for the first time, it was possible to communicate with a ship during its voyage.

The Titanic’s operators were kept busy with passengers’ notes to family and friends throughout their long shifts.

Though nearby ships did warn them of icebergs along their route, these warnings never reached the captain.

The Titanic operators used a key to tap out messages, letter by letter, in Morse code.

https://view.genial.ly/62794155136456001873f809

Tuned in

Pressing the key creates contact between the lever and the base, which completes the flow of electrical current through the attached wire.

The operators received the length and arrangement of these ‘interruptions’ — dots and dashes — and decoded them into text.

This Marconigram, received by the Celtic, reads:

CQD require assistance position 41.46N 50.14W struck iceberg Titanic.

The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS. Marconi 263

‘CQD’ was the Marconi Company help signal before the universal adoption of SOS in 1914.

‘CQ’ alerted all stations that a message was incoming, with the ‘D’ for ‘distress’.

The front page of The New York Times, 17 April 1912, reporting the ongoing wireless search for Titanic survivors

More Marconi stories

Book a free Museum ticket

Marconi was quick to adapt and improve on the discoveries of fellow scientists

The coherer, which detects radio waves, grew out of Edouard Branly’s 1892 discovery that loose metal filings in a tube clump together when exposed to a small radio frequency current.

https://view.genial.ly/629b289fed0ec50017acab65

Tuned in

In 1895, Augusto Righi developed this oscillator to generate a visible electric spark and invisible radio waves.

Tuned in

Marconi used his own coherer receiver, along with the Righi Oscillator, in a demonstration at London’s Toynbee Hall in 1896.

Telegrapher William Preece operated the oscillator on stage, while Marconi carried the closed coherer receiver around the room.

Tuned in

To the amazement of the audience, sparks connecting the metal globes of the oscillator caused the bell on top of the coherer receiver to ring, even though nothing visibly connected them.

Early radio receivers detected radio transmissions and converted them into the dots and dashes of Morse code.

This telephone earpiece is the one Marconi used for the first transatlantic radio transmission in 1901.

He connected it to a coherer and held to his ear — like a modern telephone.

Tuned in

More Marconi stories

Book a free Museum ticket

After World War One, Marconi‘s engineers wanted to explore the potential of wireless technology to educate and entertain

That meant moving away from the beeps of telegraphy and turning instead to the speech and music of telephony.

By 1920, the Marconi Company had developed the technology for this new form of radio broadcast.

The world was listening — but what would they hear?

Family listening to the radio, 1921. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, LC-H234- A-9968.

The BBC

To Educate and Entertain …

Advertised as Marconi’s most popular receiver, the V2 came onto the domestic market shortly after the BBC was founded.

https://view.genial.ly/629b72a6e733fb0010d4f605

Tuned in

Two listeners could each use headphones to hear the broadcast at the same time — or with the addition of an amplifier and speaker, the sound could fill the room for everyone to enjoy.

Tuned in

By 1930, over 3 million radio licences were in use — that’s roughly one in every two homes in the United Kingdom.

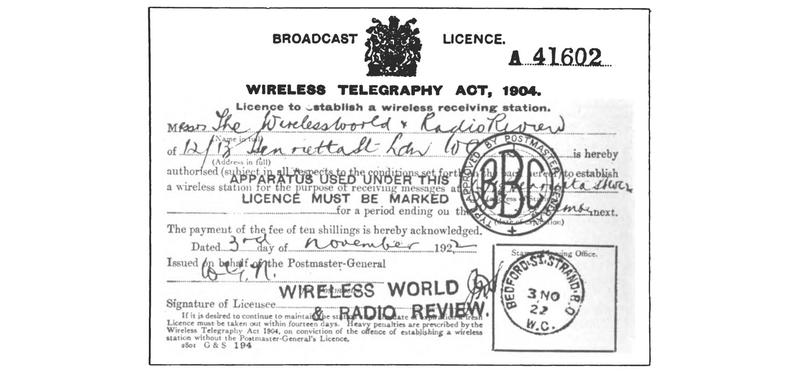

This is a licence for a radio receiver granted by the BBC — then part of the British Post Office — on 3 November 1922.

A licence for a radio receiver granted by the BBC — then part of the British Post Office — on 3 November 1922

Only receivers with a stamp like this were legal to sell in Britain. An annual licence cost 10 shillings — about £30 today.

Diva on the airwaves

World-famous soprano Dame Nellie Melba used this microphone in the first ever live musical radio performance, sent from a small packing shed at Marconi’s Chelmsford factory on 15 June 1920.

Tuned in

Marconi advertised the time and frequency of the performance ahead of time, which meant people all over Europe — and as far away as New York City — could hear and enjoy Melba’s performance.

The cone-shaped wooden mouthpiece funnelled the sound waves Melba’s voice created into the transducer, which converted them to electrical signals.

Those signals passed through the wire to a transmitter, which broadcast them over the wireless frequency.

Listen to the British Library's recording of Dame Nellie Melba's historic broadcast

Are you receiving me ...?

This small object was an alternative to the heavy, home-based radios that flooded the market in the 1920s.

At 1/50th of the cost of a full home system, it was also much more affordable.

Tuned in

The Baby Crystal Receiver has extremely simple circuitry and needs no power supply — just attach an aerial and an earth connection, plug in a pair of headphones and start listening!

On the Home Front

During World War II, radios became the centre of life on the home front.

Families could tune in to BBC news broadcasts and a range of programmes that lifted the national spirit.

After the war, domestic radios like this one brought public figures from the worlds of politics and show business into the homes of ordinary people.

The simple design and clear labelling made it easy to use.

Tuned in

The dials and display at the base of this radio allowed families to tune in to different radio frequencies, identified by place and 3-letter call sign. “Daventry”, which appears multiple times, was used for BBC broadcasts, including the:

-

Light Programme (popular music)

-

Third Programme (classical music), and

-

The Home Service (news and current events).

More Marconi stories