The travels of an astrolabe: Kabul to London

Dr Sumner Braund traces the Shah Abbas II astrolabe's journey from Kabul in the late 1800s to the salerooms of 1920s London.

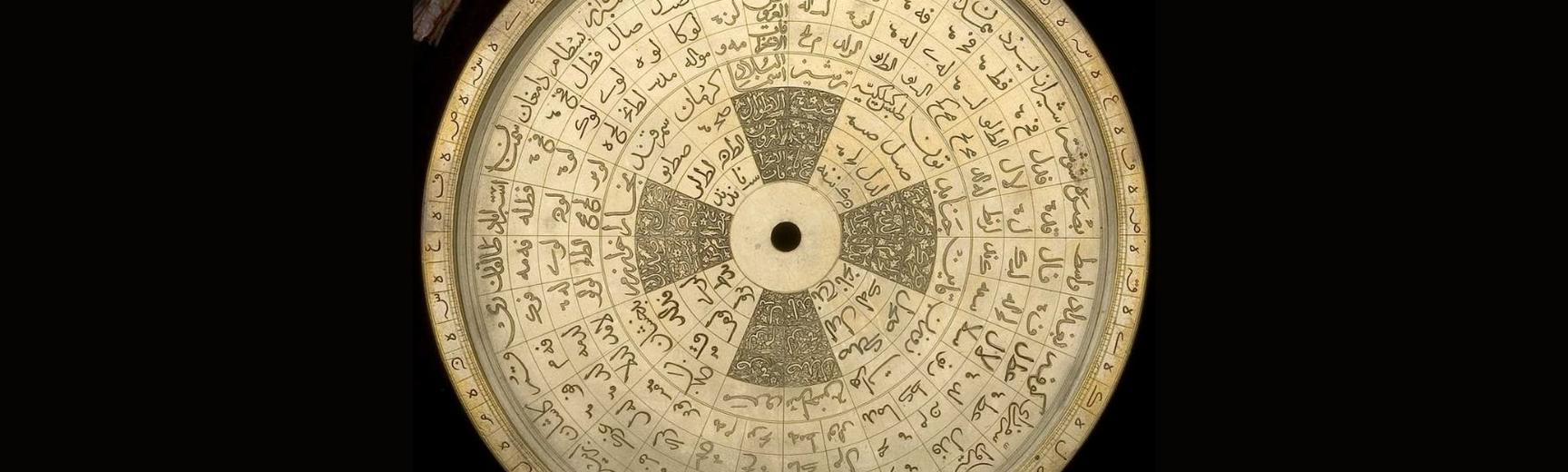

As I explored in my previous post, there are many roads which the astrolabe dedicated to Shah Abbas II could have travelled to reach Kabul.

What we do know is that by the late 1800s, it was kept in the fortified palace of Kabul, known as the Bala Hissar.

And the reason we know this is because, in 1879, a British colonel removed it from the Bala Hissar after the British army captured the city of Kabul.

Working backwards

That's why my investigations often begin with what we do know at two points in time:

start: who made the object and/or owned it first

end: who sold the object to Lewis Evans.

My mission is — as far as possible — to fill in the gaps between these owners.

With this astrolabe, we can only take a limited number of steps forward using the knowledge of its original owner (Shah Abbas II) and maker (Muhammad Muqim al-Yazdi). So let’s turn in a different direction and work backwards from Lewis Evans.

In November 1921, Lewis Evans bought the astrolabe from Percy Webster, his preferred dealer in historic instruments. At £200, it was an expensive purchase, (the equivalent of around £9,440 today).

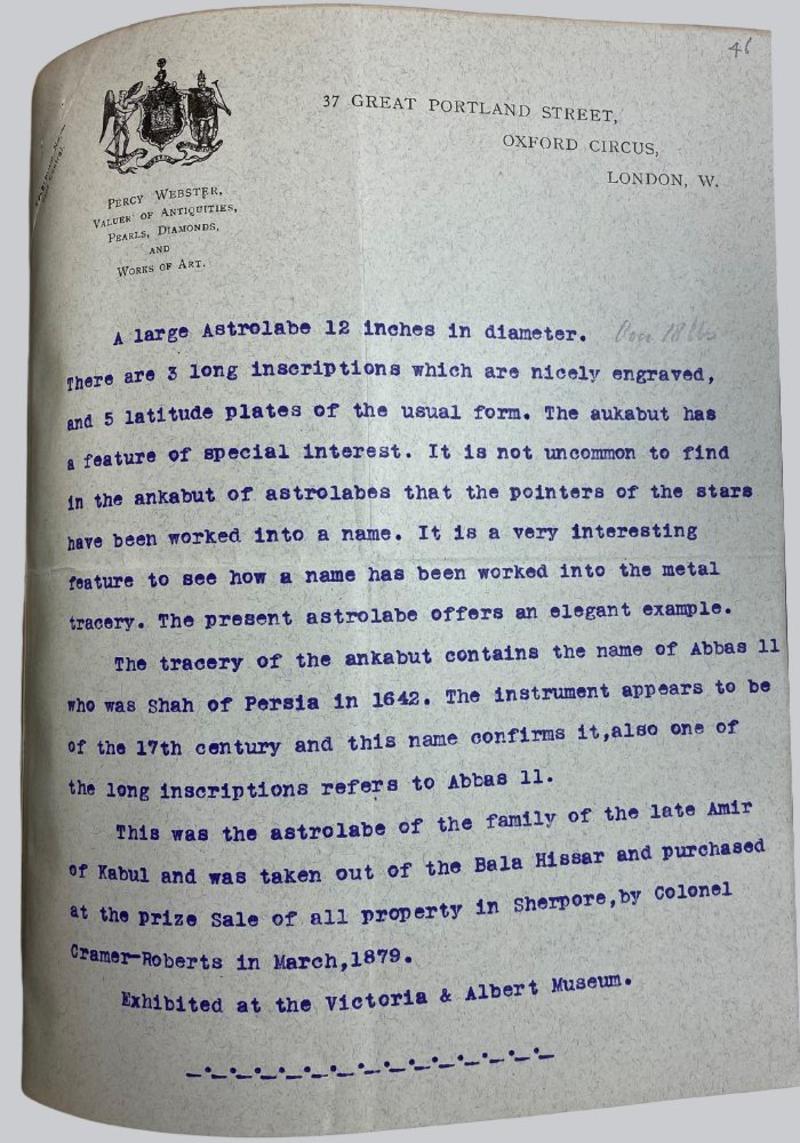

Webster provided a description of the instrument to certify its origins:

‘This was the astrolabe of the family of the late Amir of Kabul and was taken out of the Bala Hissar and purchased at the prize sale of all property in Sherpore, by Colonel Cramer-Roberts in March 1879’, Percy Webster to Lewis Evans, 8 November 1921, History of Science Museum, Evans MS 78 fo. 46.

This description provides us with several important facts:

Who: the names of two owners — the family of Sher Ali Khan and Colonel Cramer-Roberts.

When: a date — March 1879.

Where: a place — Bala Hissar, Kabul.

This was my starting point. From here I was able to reconstruct the painful colonial extraction of this instrument from its Afghan owners in the 1800s.

Who was Sher Ali Khan?

Let’s start with the first owner from the 1800s named by Percy Webster: Sher Ali Khan.

On the death of his father Dost Mohammad Khan in 1869 CE, Sher Ali Khan became the Amir of Afghanistan.

Over many years and conflicts, Dost Mohammad Khan had created a central government over the diverse groups in Afghanistan, declaring himself Amir in 1838 CE.

Following Dost Mohammad’s death, Sher Ali Khan inherited a dominant position, complete with powerful international “allies”.

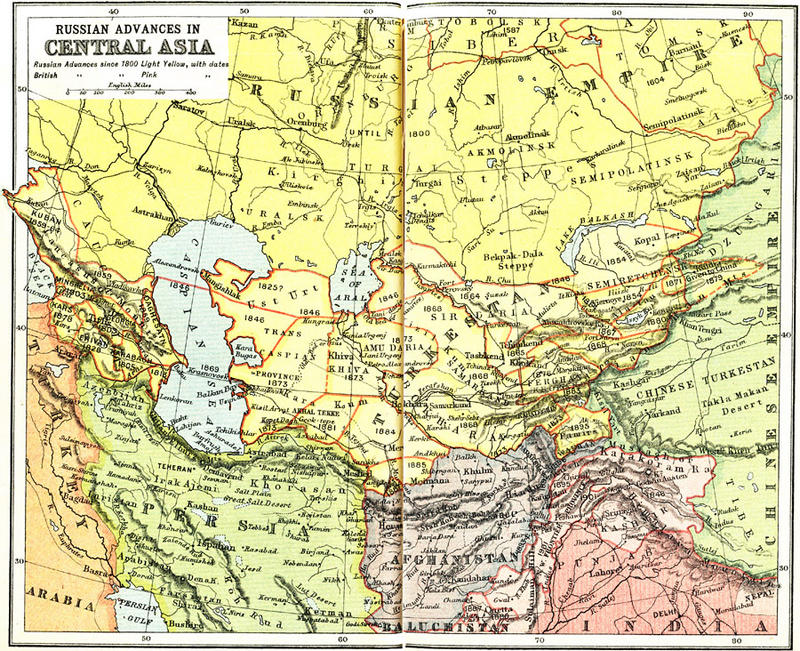

Since the beginning of the 1800s, the British and Russian empires had been vying for influence and control over various regions in Central Asia.

Criss-crossed by lucrative trade routes, these territories provided new markets for British and Russian goods.

And for the British, Afghanistan represented an important buffer between the British Empire in India and the Persian and Russian empires.

Russian and British Expansion in Central Asia, 1800–1912 Map courtesy FCIT. https://etc.usf.edu/maps

It was the British empire's intervention in the conflict between Dost Mohammad Khan and his political rival — when they sided with Shah Shujah over Dost Mohammad — that initiated the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-1842 CE).

The British suffered (in their eyes) humiliating losses in this war and committed violent acts of reprisal, including the destruction of Kabul’s bazaar. Ultimately, Dost Mohammad returned to power and maintained tense — but cordial — relations with the British Empire in India.

Dost Mohammad’s son, Sher Ali Khan, followed in his father’s footsteps in more ways than one: during his reign, the British initiated the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-1880 CE). Sher Ali was not as successful as his father and did not hold on to power. Deposing Sher Ali as leader, the British replaced him with his son, Yaqub, who they believed was more amenable to British influence.

In September 1879, the British envoy in Kabul, Sir Louis Cavagnari, was killed. Major-General Frederick Roberts was sent to Afghanistan to identify those responsible and any other suspected rebels against British influence. In October, Frederick Roberts took Kabul, destroyed part of the Bala Hissar in a punitive action and began a series of trials and executions.

During the sack of the Bala Hissar, Major-General Roberts discovered many precious items, like this painted miniature:

It is possible that the astrolabe was taken out of the Bala Hissar at this point.

It may also have been removed from the palace in December 1879, following the siege of Sherpore Cantonment which ended in British victory and the abdication of Yaqub Khan.

Percy Webster’s provenance record hints at the brutality of this succession: treasure from the Bala Hissar — including the astrolabe — was taken out of the palace and sold at a prize sale in Sherpore, the British military base just outside the city of Kabul. The precious property of Afghan royalty was laid out for enemy soldiers to purchase.

It was in this context that royal goods came into the hands of a British officer from Norfolk.

Who was Colonel Cramer-Roberts?

Percy Webster’s provenance record claimed that Cramer-Roberts bought the astrolabe at a prize sale of looted property in March 1879.

It is possible to corroborate this statement with various sources from the time. Cramer-Roberts’ obituary — published in The Times in 1895 — noted that he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in 1884 and then to Colonel 1885. It suggested that these promotions were due, in part, to his exemplary service: he received a medal with clasp for his service in Afghanistan, notably for his efforts at Jagdalak and in the relief of Sherpore.

Both of these events were reported in The London Gazette at the time, though it appears that Webster mis-reported the month – March 1879 was a brief period of respite during the Second Anglo-Afghan War, and British forces captured Kabul in October of that year.

Prices are not generally high at a prize sale, and perhaps Cramer-Roberts was given a favourable deal in recognition of his efforts to help the British who were besieged at Sherpore, outside Kabul, in December 1879.

We can't be sure, because no further record of the transaction survives.

But it is clear that whatever the circumstances – award for service or self-motivated purchase – Cramer-Roberts valued this astrolabe. He found a way to transport the 8.5 kilogram brass object back to London and kept it until his death in 1895.

Cramer-Roberts’ probate record reveals that he died a wealthy man: at his death, his son, John – who had also joined the military – inherited just over £11,000: the equivalent today of £1.3 million.

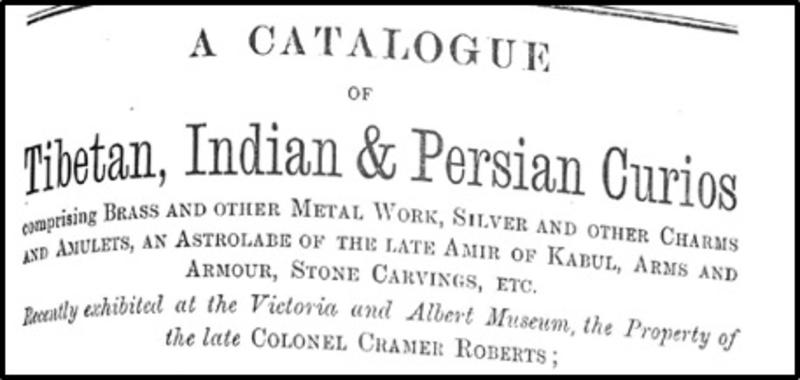

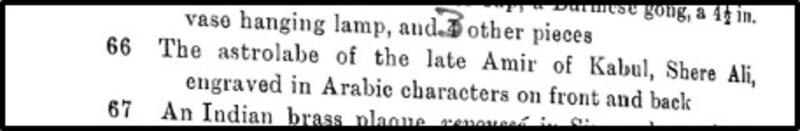

In 1921, John sold his father’s collection of “Tibetan, Indian, & Persian curios” at the Foster’s Sale Rooms. The sales catalogue reveals that this collection totalled 66 objects, many of them from places where Cramer-Roberts had been posted over his 36 year-long career in the military.

The Shah Abbas II astrolabe was sold to Percy Webster as Lot 66 for the sum of £57 and 15 shillings (£2,726.00 in today's money).

Extracts from Foster’s Sale Catalogue, 27 October 1921, now held by the National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum

Cramer-Roberts’ wealth on his death, combined with the breadth of his collection, suggest that whatever the price of the astrolabe in 1879, he was willing and able to pay it.

Record keeping

The reconstruction of this “purchase” — extraction might be a better word for it — is possible because Lewis Evans made sure to record it.

I think that, in Evans’ eyes, the provenance record was valuable because it emphasised, and authenticated, the prestige of the astrolabe’s history. Not only was this an astrolabe dedicated to — and owned by — the powerful Persian emperor, Shah Abbas II, it was also kept in the treasury of another royal family: the Barakzai Amirs of Afghanistan.

Cramer-Roberts’ role was important for Evans to record because it acted as the corroboration to that fact: a British colonel had himself taken the astrolabe from the palace where it had been most recently kept.

And that brings me to my final point. When we consider the cultural heritage visible in our museums, we should remember that there are many agents in the dispersal of historical objects, including those who take and those who acquire.

What do you think about the journey of this regal astrolabe from its origins in Safavid Persia to a European museum?

I’d love you to share your thoughts and join the conversation.

May 2023

Dr Sumner Braund

I’m a historian of early medieval England with a passion for museums and archives.

As Research Fellow on the Finding and Founding Project, I am putting investigative skills to work as I uncover the provenance history of the History of Science Museum’s founding collection.

This work has already taken me to archives in the UK and the US, from nineteenth-century letter collections to sales registers to military dispatches.

For me, history is the study of people – and the objects that I am currently investigating are taking me on a global journey to people past and present.

Share on social media

If you'd like to share this post on social media, just copy this link:

https://www.hsm.ox.ac.uk/finding-and-founding-blog-three-the-travels-of-...

and go to your chosen social media channel:

Comments

As always, we’re interested to know your thoughts, so please share your comments with me:

![An Afghan Sirdar [officer] and a British soldier, 1841 (c) Watercolour on Oriental paper, by an Afghan artist. National Army Museum, NAM 1983-07-11 An Afghan Sirdar [officer] and a British soldier, 1841 (c) Watercolour on Oriental paper, by an Afghan artist. National Army Museum, NAM 1983-07-11](https://www.hsm.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/mt_image_medium/public/mhs/images/media/an_afghan_sirdar_officer_and_a_british_soldier_1841_c_watercolour_on_oriental_paper_by_an_afghan_artist._national_army_museum_nam_1983-07-11.jpg?itok=4-pz3VTC)